Yesterday, Tomorrow

April 19th, 2025, we had a little bit of Lechon left over: legs, spine, ribs, and a few pieces of belly, since the head was claimed the evening before. I scoured the fridge, looking for vegetables I could pair with these leftovers. Not much it seemed, but in my freezer, there were Thai chili peppers, icy with freezer burn, green beans, ginger, and on the counter, garlic and onion. I turned to face the disembodied pieces of the carcass and pulled it from the aluminum pan, and with quick work of my knife I carved what little meat was left on the bone and diced it up into smaller pieces, a small mound growing on my chopping board. A quick wash and the vegetables were next, still frozen. I finished with a sweep of scraps landing in the trashcan, and at the sink the soap cleansed the residue from my fingers.

As I procured my wok from the cabinet, a kitchen tool not wielded lightly, with the wide brim carbonized along the edges, I thought about the many meals that had been made inside. Atop the stove, the flames licked up as high as they could, heating the steel so hot that the oil smoked on contact. In went the meat, sizzling and splattering up the walls of my pan, and with my spatula I tossed the contents, and they arced through the air. I had little time to work as the lechon was quickly browning on the fire, so I scraped my aromatics into a bowl and added it to the dark maw of the hungry beast.

The smell of ginger and garlic filled the kitchen as steam rose from the wok, while the chilis tickled the back of my throat. Toss, toss, mix, toss, as I held the wooden handle steady, concentrating, my lips pursed. In goes the green beans, very last so not to take too much away from the building heat. Toss, toss, mix, toss, and in goes the soy sauce, fish sauce, mushroom sauce, coating the food and creating a glossy sheen. Just a few more minutes and the meal would be ready, the beast already having her fill.

The pan is heavy as I transfer the food into a dish, it lands back on the stovetop with a metallic clang.

“Kain na, tayo!” I call out to the house.

Mealtimes hold so much weight in my life, whether they are large or small. They are a moment of recouperation when the day is hard, a moment to re-energize when morale is low, a treat, a space to come together and connect with the people in your life, they are also necessary to survive, since we all need to consume in order to live. The vignette above describes the day after my reception, but it is also a moment I’ve relived many times; for a while, intergenerationally, lately just two, and recently for a crowd of over 200. A pan, some protein, some aromatics, and some sauce, coming together with intention and heat in order to fuel the people in the place I live.

My research for the past three years of this MFA program has been rooted in the philosophy of Kapwa, an indigenous principle that has persevered generationally through the colonialization and globalization of the Filipino people. The Filipino worldview can be defined as a culture of deep interconnection and shared identity, a oneness between humans and nature. The catch is, there is no direct translation to English, and because of my American upbringing through the Filipino diaspora, I sought to identify the ways that Kapwa was evident in my life.

With my parents, brother, and sister, we would sit together at a table for every meal, sharing the labor in preparation for our food, and with my grandparents, we harvested our vegetables from the garden in the backyard. After we ate, the scraps would return to the earth, buried under the roots to cycle back nutrients for the plants we tended. With our Filipino community members, I saw a kinship that was always welcoming, and when invited into their home, the guests were always presented with something to eat. According to Virgilio Enriquez, the father of Filipino Psychology, “What the Filipino eats, the sources of his food and the way it is prepared and served indicate a relationship between man and nature as intimate as it is practical. Food or eating is not only a biological imperative. It is a social necessity and socially defined phenomenon of sharing which fosters goodwill and friendship,” (Enriquez 2) and in my eyes, this ritual of preparation, a combination of nature and nurture, was an important part of the ritual of community.

I reflect on the feeling of place and placelessness as a parallel to my family’s migration story, one that is similar across immigrant communities, displaced communities, and marginalized communities. I think of the banana tree that I first saw planted in the soil during a Wisconsin summer, thriving temporarily in the decorative space of the Allen Centennial Garden. There was an inevitability to its existence, eventually it would perish along with many other plants as the weather turned and winter settled, but its belonging in the landscape was questionable to begin with.

I found myself deeply connected to the banana tree, due to its tropical origins existing in a northern landscape, being new to the environment myself. I inquired the garden staff about what lay in store for these trees once winter came around. I was told it would be tossed into compost. Balking, I asked if I could take them. Would it survive the winter? What is necessary for its survival? What is necessary for mine? I struggled to answer these questions, especially as I attempted to keep the banana tree alive. I purchased soil, cut leaves from the stalk to preserve its sugar stores, and kept it in a dark area. But even with my good intentions and hopeful nature, it would eventually perish due to my lack of proper resources and time.

For Magmula sa Lupa, I brought my audience into the “Filipino worldview” and led an event for the community, celebrating the building and shared labor of community, through my connection with the banana tree and its journey through globalization and cultivation. It became a vessel that helped fill the gaps in my practice; by paralleling the way my family legacy has been shared with me and applying that to my current landscape. While the leaves of the banana tree are useful for shade and the wrapping of food, when it matures and bears fruit, its death is not far behind. Its canopy wilts, falling to the floor, creating ground cover for the roots, giving back to the soil, and it will push out a new pup, with DNA that mirrors its predecessors to continue the cycle.

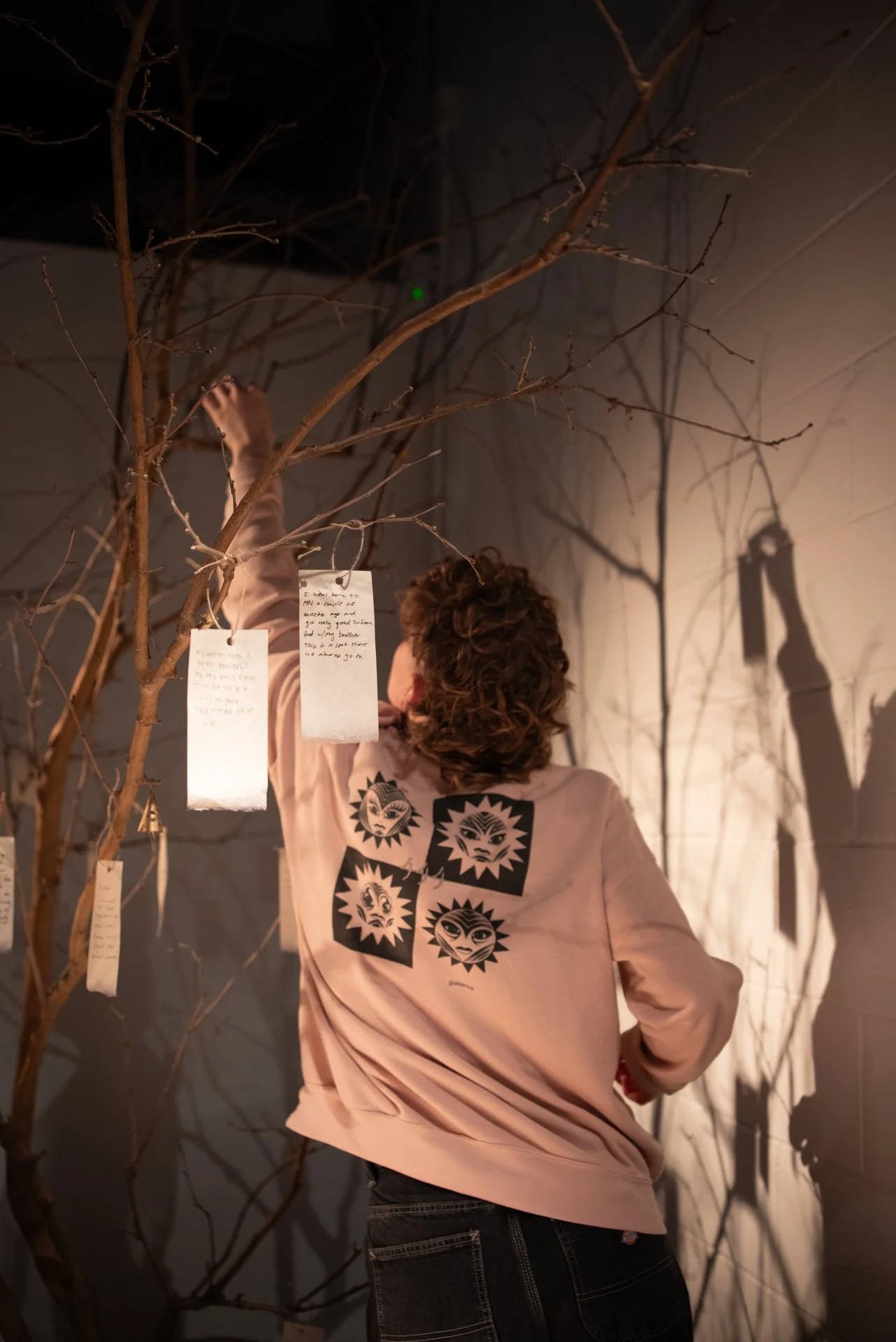

My goal was to leave behind a memory that would continue to live sensorially with the audience long into the future, in hopes that the spirit of the work could transcend to the people’s own network and communities. I worked collaboratively with members from the Philippine-American Association of Madison and Neighboring Areas (PAMANA) and the Filipino-American Student Organization (FASO) to help make food, pancit, Filipino desserts, contributing rice, and physical help, to welcome the people attending my Kamayan feast, since these established communities had already fostered the Filipino Worldview as a tool to find each other and their support. Banana leaves were contributed by the Olbrich Botanical Gardens, Allen Centennial Garden, and the Botany Department, as a foundation for the food and for the community to gather around. Additionally, I collaborated with Kirk Smock, the founder of a small local bakery called Origin Breads, to create a Pandesal that was entirely localized to the landscape of Madison. Much of the physical work was created in tandem with other artists as well. For the room divider in the gallery, titled Passages, my partner Isaiah helped me map out the design, woodworker Corey Wellik fabricated the entire vessel, printmaker Maya Srinivasan assisted me in laying all the prints inside of the frames, and sculptor Paulina King helped me with assemblage. One of the other pieces, The Memory Tree was a branch from an invasive white mulberry growing on Epic’s campus brought in by friend and horticulturist, Jarret Miles-Kroening, and the tags hung on the tree were cut by Erin McAdams and Kagen Dunn, from scraps of prints made for “Passages.” My wish was to ask the audience to hang their memories of comfort foods, contributing to a participatory sculpture. The table that stood as the stage and platform for my performative carving of the roast pig was fabricated and designed by Jack Sherry, and the entire room was lit by sculpture artist Henry Burke. Claire Tomkiw helped me design the zine handout, Abel Broyles handled printing, and Jason Houge and Isaiah helped fold all 100 of them. Nia Scott, Aaron Granant, and Jami Balicki, documented show. I saw my own contribution as an organizer, the conceptualizer, the host, the gardener, helping to build an environment for relationships and memories be cultivated, and consider everyone listed above as a part of the work, contributing to the larger sense of Kapwa, and building mindfulness to the connection to food, the Earth, and each other.

Considering the shift in my practice from photography, to installation, to performance and social practice in only a few years’ time, my goal isn’t to settle on one form of making — but to utilize the most appropriate and impactful method for place-based investigations of belonging, identity, and community, to build relationships and sensorial memories. I don’t believe I’ve landed on a resolved form, as I pull from the seasons of past projects and integrate them into my current work; like creating a new meal from leftovers, or keeping scraps meant for compost, these memories I’m pulling from the past continually fuel the future.